|

Indonesians don't want foreigners meddling in their

affairs. But that doesn't mean the U.S. can't-and shouldn't-try

to prevent the country sliding into further chaos

By Melinda Liu

NEWSWEEK WEB EXCLUSIVE

May 17 - The first point to remember about Indonesia is this: it's

an important country-and it's going to be very messy for a very

long time.

INDONESIA IS OFTEN ECLIPSED by its more vocal neighbor, China, or

its more prosperous Asian colleague, Japan. Yet Jakarta is the capital

of the world's fourth most populous nation-and its most populous

Muslim one-with 210 million people, more than 13,000 islands and

300-plus ethnic and linguistic groups. Indonesia also dominates

strategic shipping lanes which provide passage to 40 percent of

the world's commerce. It's a key oil and gas producer, an OPEC member,

and a host to Western corporate giants such as Exxon Mobil, Caltex,

Freeport-McMoran and British Petroleum.

The U.S. government regards Indonesia's painful implosion with urgency

and alarm. During his recent Senate confirmation hearings, James

Kelly, the new assistant secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific

affairs, warned that Washington needs to support the territorial

integrity of the Indonesian archipelago lest the world wake up one

day to find a "fragmented Indonesia that feeds fundamentalism,

narrow regionalism and movements that, to put it most charitably,

are very unstable and very dangerous."

WINKING AT CORRUPTION

The second key point is that, despite Indonesia's importance to

Washington, there's not much the U.S. can do to orchestrate policy

there. The violence and disintegration now evident in Indonesia

has had a long gestation period. They are the legacy of decades

of Western financial support for Jakarta's authoritarian leadership,

which left little space for civil society. The West winked at the

corruption of President Suharto, the army general forced to resign

in 1998 after three decades of rule. Western governments tolerated

rampant human-rights abuses by the Indonesian military. They supported

Suharto's destructive social experiments, such as the massive transmigration

schemes that played mix-and-match with disparate ethnic groups-the

same groups that are now massacring each other over grim, decades-old

feuds.

In spite of these problems, Indonesia's elite does not want foreigners

to meddle in their affairs-no matter how messy those affairs may

get. "We Indonesians want to solve problems ourselves,"

says political analyst Andi Mallarangeng. "I ask the U.S. to

stay out of our business."

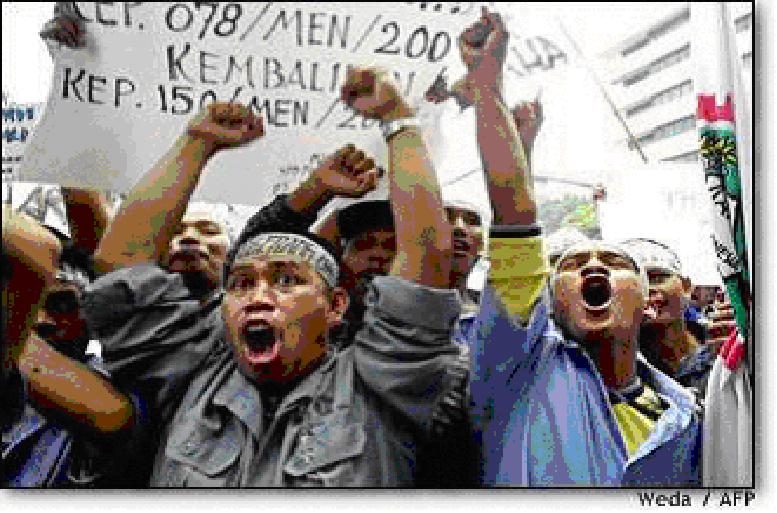

The occasional dose of candid rhetoric from Washington's current

ambassador to Jakarta, Robert Gelbard, has prompted howls of outrage

from Indonesian politicians, regular protests outside the American

embassy, and a nickname for Gelbard as "Ambo the Rambo."

Washington, however, must still look after U.S. interests in Indonesia.

And the Jakarta government certainly isn't doing much to help on

that score. Indonesia suffers from a paralyzing leadership vacuum,

with embattled President Abdurrahman Wahid dwelling in a twilit

state of denial, pooh-poohing calls for his resignation as "just

politics" and reassuring himself that grassroots crowds still

adore him.

WAITING FOR MEGA

Wahid seems to ignore mushrooming support for his departure from

office-and especially signs of growing impatience from his presumptive

successor, Vice President Megawati Sukarnoputri. Yet Mega herself,

as she's called, is too inexperienced in economic affairs-an area

in which Indonesia sorely needs leadership-and too cozy with the

country's generals to ease Washington's misgivings. Even many Indonesians

know the country's current crop of leaders "is not perfect,"

admits Mallarangeng. "But we must give them a chance, he says.

"There's no guarantee with Mega, but there's absolutely no

hope with Gus Dur [the popular nickname for Wahid.]"

Even the once-monolithic military-the brutal but efficient enforcer

of Suharto's day-is now sullen, demoralized and fragmenting. As

for democratic institutions, Indonesia never had any before Suharto's

1998 ouster. Today many such institutions are embryonic at best.

Deadly bombings have gone unsolved. Convicted economic criminals,

such as Suharto's son Tommy, remain at large. Massacres erupt without

anyone being held accountable. "In order to cement democratic

institutions, you need a functioning and independent judiciary,"

says one Western diplomat in Jakarta, "You just don't have

that here."

The result is that many Indonesians are taking the law into their

own hands. In February, supporters of the Indonesian president went

on a destructive rampage to show their displeasure after Wahid was

censured for alleged involvement in two financial scandals. In early

March, Muslim residents of Ambon, capital of the strife-torn Malukus,

invoked Sharia (Islamic law) and stoned to death a 30-year-old Islamic

warrior for raping a girl. Muslim leader Jafar Umar Thalib, who

heads a militant Islamic group called the Laskar Jihad, was detained

by investigators looking into the death. But his supporters argue

that the death penalty is "an integral part of Islamic teaching

and an expression of religious freedom."

LIMITED OPTIONS

Against such a backdrop, Washington's options are limited. But with

a new U.S. administration in place, it is essential to examine those

options closely-and make adjustments before more chaos erupts.

What can the Bush team do to help Indonesia?

Its first step should be to help strengthen and develop democratic

institutions. Already the U.S. is helping train an Indonesian police

force independent from the military. The separation of the police

and the army is a post-Suharto reform that remains crucial to the

country's long-term democratization. Yet the civilian law enforcers

remain undertrained, ill-equipped and hampered by a massive inferiority

complex.

The second step should be to re-examine relations with the Indonesian

military. A problem here is that Washington has little room to maneuver

because the U.S. Congress has responded to the Indonesian army's

shabby human-rights record by placing bans on bilateral exchange.

For now, the U.S. military can interact with its Indonesian counterpart

solely in humanitarian exercises.

And yet one source of long-term leverage over Jakarta's brass-especially

younger officers rising up through the ranks-is precisely through

close ties, training and transmission of a more enlightened "military

culture." James Kelly, the State Department's new Asia guru,

has warned clearly that "by isolating the Indonesian military,

the U.S. is forfeiting its influence over it."

SIDESTEPPING CONFRONTATION

Still, Kelly neatly sidestepped a confrontation with the Congressional

bans during his Senate confirmation hearing by simply stating it

was hard to imagine Indonesia holding itself together without military

cooperation.

A third step is for the U.S. to make it clear that it will not help

the various secessionist movements in their struggles for independence.

The international community set an awkward precedent after Suharto's

fall when it helped pressure Jakarta to grant independence to East

Timor, a one-time Portuguese territory invaded by the Indonesian

military in 1975. Now other separatist leaders-especially in oil-rich

Aceh and Irian Jaya, which has vast copper and gold mines-argue

that "any other area that has been colonized by the Indonesian

government has the right to its independence," as an Acehnese

rebel commander recently put it.

But with literally hundreds of discrete ethno-linguistic groups,

Indonesia could keep unraveling indefinitely if the separatist trend

were to gain momentum. Washington can express sympathy with ethnic

concerns and support government moves toward granting regional autonomy.

But unless the Bush administration has the stomach to bankroll and

baby-sit a proliferation of dependent Southeast Asian protectorates,

it needs to make clear that Yugoslavia-style disintegration is not

in the U.S. interest

A fourth measure is for the U.S. to enhance counterterrorist measures,

including training for the Indonesian police. As the chaos deepens

in Indonesia, U.S. citizens and businesses could become the focus

of Islamic extremists seeking soft targets. Already there are more

than four organizations in Indonesia linked to international terrorist

Osama bin Laden, according to a foreign diplomat in Jakarta, and

Indonesian mujahedin, or Islamic holy warriors, have trained in

guerrilla camps in Afghanistan and the southern Philippines.

"Two things happen when authoritarian governments fall in Muslim

countries," says the Western diplomat. "People gravitate

toward Islamic fundamentalism, and Islamic extremists gravitate

toward the country."

OPPORTUNITIES FOR EXTREMISTS

To be sure, Indonesia's government has remained strictly secular

throughout its history as a nation. And the country's brand of Islam

is a syncretic, moderate form that does not usually encourage militancy.

Still, the ferment in Indonesia and the tattered state of law enforcement

could provide an opening for opportunistic Islamic extremists of

the sort who executed the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Africa.

Then there's a final cautionary note. Some officials in the new

American administration want to revamp the IMF's policies in Asia.

The IMF overreached in the '90s, and its own officials admit to

having meddled too deeply in Indonesia. "No one, including

the fund, can judge itself free of part of the responsibility for

this tragedy," the new IMF managing director Horst Kohler said

recently. George W. Bush's team includes advisors who, at least

in the past, were disdainful of multilateral financial solutions.

(Treasury's new undersecretary for international affairs, John Taylor,

once suggested abolishing the IMF altogether, for example.) In 1998

the Treasury Department's decision to overrule an IMF proposal to

prop up the ailing rupiah helped send the Indonesian currency into

free-fall-and helped bring down Suharto's regime.

Now, once again, Indonesia is cause for great IMF concern. A $5

billion IMF-led bailout for Jakarta has flopped. The IMF has yet

to disburse a crucial $400 million credit tranche, due last December,

because Jakarta has failed to implement promised economic reforms.

The IMF's stand, in the face of Indonesian recalcitrance, will play

a significant role in the unfolding political drama. But if Washington

doesn't proceed cautiously, a full-fledged Indonesian economic collapse

could threaten to destabilize the entire region

Source

|

|